It was 1975 when Sinclair v Maryborough Mining Warden changed the future of our beaches and mineral sand mining forever. High Court Chief Justice Sir Garfield Barwick together with Justices Gibbs, Stephen, Jacobs and Murphy made their feelings about the lawfulness of mineral sand mining decisions by the Queensland Government very clear.

“5. In conclusion I would, with respect, adopt what was said by Lucas J. in the Supreme Court, that the courts are not concerned with the question of the desirability of permitting sand mining to take place or with the question whether the recommendation of a warden is right or wrong, provided that he has performed the duty cast on him by the law. In the present case the warden failed to perform his duty and should therefore now be directed to proceed with the hearing in accordance with the provisions of the regulations. (at p483)”

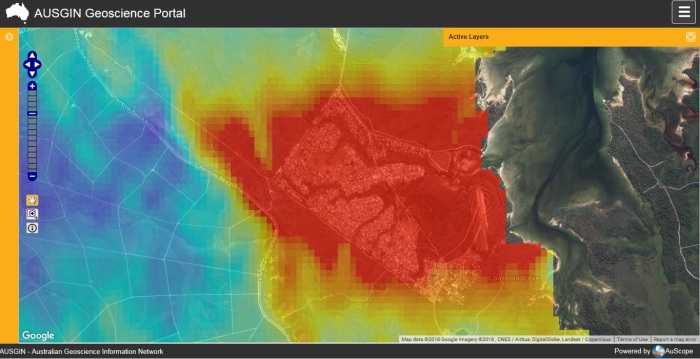

From Cooloola, Dunwich, Gold Coast and Currumbin in Queensland to Byron Bay, Mooball, Woodburn, Jerusalem Creek and others in New South Wales, mineral sands were mined, concentrated and stockpiled. Because mines varied in their mineral composition and miners targeted different minerals over the decades, both monazite (thorium), xenotime (uranium) and other minerals were returned to particular areas of the mineral sands operation and other sites as waste. Some of this material was even used as public and private land fill. These places where mineral sand waste was stockpiled or buried during late-19th and 20th century sandmining operations are visible today in Radiometric imagery.

From Cooloola, Dunwich, Gold Coast and Currumbin in Queensland to Byron Bay, Mooball, Woodburn, Jerusalem Creek and others in New South Wales, mineral sands were mined, concentrated and stockpiled. Because mines varied in their mineral composition and miners targeted different minerals over the decades, both monazite (thorium), xenotime (uranium) and other minerals were returned to particular areas of the mineral sands operation and other sites as waste. Some of this material was even used as public and private land fill. These places where mineral sand waste was stockpiled or buried during late-19th and 20th century sandmining operations are visible today in Radiometric imagery.

Cooloola Cove (QLD)

As stated in an article by Byron Bay Historical Society:

“Much concern accompanied the disposal of ‘radioactive waste’ from the processing plant. This radioactivity was caused by monazite, a thorium-bearing, resistive, heavy mineral contained in the black sand concentrated from the beaches. In the early years after WWII the Australian Federal Government mandated that this mineral be recovered and stored by the sand miners as thorium was a potential fuel for nuclear power generating stations. Ultimately uranium became the preferred fuel and most mineral sand producers were left to dispose of any monazite they could not sell. Sand miners either mixed it with normal sand and buried it or returned it to the beach whence it came.” https://web.archive.org/web/20170310191149/http://byronbayhistoricalsociety.org.au/development-of-byron-bay/population/

Brisbane and Dunwich (North Stradbroke Island, QLD)

Gold Coast QLD)

Currumbin (QLD)

Byron Bay (NSW)

Mooball (NSW)

Woodburn (NSW)

Jerusalem Creek

This is quoted from NSW National Parks and applies from Tue 18 Jul 2017, 7.00am to Tue 30 Jun 2020, 5.00pm. Last reviewed: Tue 15 Aug 2017, 1.12pm

“Safety alerts: Ilmenite stockpile removal and site rehabilitation

Visitors to Black Rocks campground should expect to encounter large trucks on The Gap Road. This is part of a major project to remove a sand mining tailings stockpile from the park and restore the area to a natural ecosystem. Park visitors are asked to slow down and exercise caution while driving along The Gap Road. No works associated with this project will be undertaken on weekends, public holidays or NSW school holidays. The truck movements are expected to continue until June 2020. For more information or to report any incidents please contact the NPWS Richmond River area office on (02) 6627 0200.”

“MINERAL SAND MINING:

The gold miners who came to the Byron Bay area in 1870 and for the next two decades mined alluvial gold off the beaches extracted it from the heavy black sand and cursed this sand for filling their sluice boxes and making it extremely difficult to capture the fine gold. They threw it away in disgust little realising that within 40 years it would become very valuable indeed.

In 1934 the company Zircon Rutile Limited (ZRL), was formed in Byron Bay. It started sand mining in January 1935 at Seven Mile Beach south of Tallow Beach, and transported the black sand concentrates to its treatment plant on Jonson Street in Byron Bay (now Woolworths’ Supermarket site). In April 1935 it became the first company in the Australia to separate a clean, high-grade zircon product from the black sand. In 1943 it became the first company in the world to produce separate, high-grade rutile, zircon and ilmenite concentrates from black mineral sands. These were bagged and exported from Byron Bay to the world. The zircon was used in the foundry, ceramic and enamel industries. From rutile and ilmenite “titanium white”, used as pigment in paint and plastics, and titanium metal were derived. To conserve capital ZRL initially used “black-sanders” to scrape, dig, concentrate and stockpile the black sand from the beaches and “leads” in the dunes to be collected by company trucks. These men were paid $4.80 for a 44 hour week, lived in tents near the beach, used the sea to wash and relax in and as a source of fresh food. They kept any gold, platinum and tin they found.

By the end of World War II ZRL was mining in its own right and was the major supplier of rutile and zircon; all from Seven Mile Beach. In 1947 it expanded north to Tallow Beach, starting at Broken Head at the southern end then moved to Taylor Lakes, Suffolk Park, Tallow Creek and finally closer to Cosy Corner beneath the lighthouse.

In 1948 floating suction dredges replaced most of ZRL’s bulldozers, scrapers and trucks. Banks of spiral concentrators on these dredges separated the heavy minerals simply and cheaply from the other sand grains. Heavy mineral concentrates were pumped to the treatment plant which now operated continuously. The remaining sand was pumped back to the mined areas and in 1951 ZRL became one of the first companies to rehabilitate mined areas when it began reforming and replanting the dunes, unfortunately not with native plant species but with imported plants such as “bitou bush” which later infested many areas.

From 1950 to 1961 ZRL was the largest and most profitable producer of zircon and rutile in Australia and the world with Seven Mile and Tallow Beaches its mining focus and Byron Bay its prime treatment centre. However, in November 1961 ZRL ceased to exist; taken over by AMC. AMC and others continued mining at Tallow Beach, then moved inland, and finally to the beach and dunes at Main Beach.

Sand mining ceased in Byron in 1972 driven by opposition from conservation groups as much as availability of resources and industry economics. Processing continued until 1974 and the plant was demolished and the site cleared by 1977. Some mined areas are now incorporated in Arakwal National Park; some are public places or infrastructure and some contain private houses, commercial and other buildings. Until the mid-1960’s there was no foreshore park, no walkway, no Lawson Street and no buildings between Middleton to Massinger Streets in Byron Bay. Dunes and swamp extended inland as far as Marvell Street and the sports fields. After the dunes were mined the land was reformed, developed by government and sold as Sandhills Estate. Private dwellings, tourist accommodation, restaurants, and community structures as well as green space are now located on the mined area.

In 39 years of production more than half a million tonnes of premium mineral sand products worth more than $500 million at current prices were mined from Byron’s beaches and dunes for export to the world. Byron Bay played a pioneering, innovative and wealth-creating role in this industry.

Much concern accompanied the disposal of “radioactive waste” from the processing plant. This radioactivity was caused by monazite, a thorium-bearing, resistive, heavy mineral contained in the black sand concentrated from the beaches. In the early years after WWII the Australian Federal Government mandated that this mineral be recovered and stored by the sand miners as thorium was a potential fuel for nuclear power generating stations. Ultimately uranium became the preferred fuel and most mineral sand producers were left to dispose of any monazite they could not sell. Sand miners either mixed it with normal sand and buried it or returned it to the beach whence it came. https://web.archive.org/web/20170310191149/http://byronbayhistoricalsociety.org.au/development-of-byron-bay/population/

LikeLike

“GOLD MINING IN BYRON BAY:

In March 1870, prospector John Sinclair recovered nearly twelve ounces of gold in two weeks from the beaches at the mouth of the Richmond River at Ballina. News of his “ounce per day” discovery soon spread and by September of that year gold had been found on Seven Mile and Tallow Beaches, the two beaches south of the Cape Byron lighthouse, as well as on Main Beach east of the lighthouse. Soon after the discovery the entire coastal strip, except for a reserve between Tallow Creek and Belongil Creek was pronounced a goldfield and open to gold mining.

The gold occurred as very small, free grains within the black sand strandlines on the active beach and in old strandlines and black sand “leads” buried by the dunes behind the beach.

The “black-sanders” usually working in groups of three skimmed black sand from the beach or DUG it from the “leads” until enough was stock-piled to start gold recovery. One then shovelled the black sand into a hopper, one pumped water to wash the sand over mercury-coated copper plates and down a sluice box, and one removed the processed black sand “tailings”. It was hard, monotonous, unrelenting, physical work.

The fine gold amalgamated with the mercury on the copper plates to form “amalgam” a putty-like alloy which could be scraped from the copper plates easily. This was the most effective way to recover this fine gold. In primitive operations like these the “amalgam” would be placed in a hollow made in a pumpkin or potato, which was then placed on a shovel and roasted in a hot fire. The fire vaporised the mercury which then condensed in the charcoaled outer layers of the burnt vegetable. This was later crushed and panned to recover the droplets of mercury for re-use. The gold would remain on the shovel as grains or more rarely as a “button” if the fire had been hot enough to melt gold.

By 1890 the richer deposits had been worked out and only a few prospectors and miners remained seeking their fortune.

This gold-field was known as the “poor man’s diggings” as everybody found some gold but no one made a fortune. No mechanised operations run by large companies were developed. The average yield for each miner was between a half and one ounce of gold per week. Total estimated production from Byron’s beaches is 20-30,000 ounces. In difficult economic times such as the depression years of the early 1930’s the unemployed and desperate returned to these beaches to eke out a meagre living.

Unknown to these gold miners the black sand they discarded contained a fortune in other minerals. But it was not until 1935 that production of rutile and zircon from these beaches began.” https://web.archive.org/web/20170310191149/http://byronbayhistoricalsociety.org.au/development-of-byron-bay/population/

LikeLike

“SEARCH FOR GOLD.

Possibilities of Beach Sand.

CORAKI, Friday.

At the Warden’s Court at South Woodburn the Jerusalem Creek Proprietary Coy., a Victorian company, registered in this State, was granted six months’ suspension of labour conditions. It was stated that ten tons of beach sand had been sent to Germany for treatment. Until the result was known, no further money was available for development.” https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/16759954?

LikeLike

“1. Platinum. – The existence of platinum was first noted in New South Wales in 1851 by Mr. S. Stutchbury, who found a small quantity near Orange. Since the year 1878 small quantities of the metal have been obtained from beach sands in the northern coastal district. Platiniferous ore was noted in 1889 at Broken Hill. The chief deposits at present worked in the State are situated at Fifield, near Parkes, but the entire production in 1909 was small, amounting to only 440 ozs., valued at £1720, while the total production recorded to the end of 1909 amounted to 11,578 ozs., valued at £20,713. The matter of treating the extensive surface deposits received further attention during the year, but the difficulty of securing the necessary supply of water has not been surmounted. In September, 1909, the price paid locally for the platinum was increased from £2 17s. 6d. to £3 15s. per ounce. Attempts were made by a French company to treat the sands in the vicinity of Jerusalem Creek in the Woodburn division, but it is represented that it was found that a larger plant is necessary to enable operations to be conducted at a profit; work was therefore suspended for the purpose of raising additional capital. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/featurearticlesbytitle/CC0C058E907E3C35CA2569DE00271B1E

LikeLike

“BMR has begun a program of test surveys and laboratory investigations to establish the geophysical response of heavy-mineral deposits. As the first stage of these investigations, airborne and ground geophysical surveys were made over heavy-mineral deposits in the Jerusalem Creek area of NSW during 1975. Jerusalem Creek was chosen for the initial field investigations because of the variety and extent of heavy-mineral deposits in the area. The airborne survey (Fig. 1) was carried out over an area of 200 sq km of coastal plain south of Evans Head, and used magnetic and gamma spectrometer methods.” https://d28rz98at9flks.cloudfront.net/80924/Jou1977_v2_n2_p149.pdf

LikeLike